Very often, the acceptance of conspiracy theories also means there is a high probability of believing that fake news on social media is credible. Although it is scientifically questionable to ascribe certain attributes to an ethnic group, many psychologists have found in the past that conspiracy theories are particularly popular among the Arabic-speaking population. Statistics show that it is irrelevant whether the group lives in the Middle East region or in a western country.

Authoritarian regimes, including Russia, are using social media nowadays to portray the unprovoked Russian war on Ukraine as a David against Goliath struggle—with the Western powers as Goliath against the David of Russia. This grotesque distortion is part of a wider anti-democratic propaganda war that authoritarian regimes are waging around the world.

Conspiracy is everywhere

In the 21st century, it is no longer stories, rumors or gossip that find their way through being passed on at bazaars, at family celebrations or during a chat on the street. It is primarily the social media that have now taken on the role of a catalyst, especially among younger population groups.

A leading psychologist, Matthew Gray, says: “Conspiracism is an important phenomenon in understanding Arab Middle Eastern politics …” Variants include conspiracies involving Western colonialism, Islamic anti-Semitism, anti-Zionism, superpowers, oil, and the war on terrorism, which is often referred to in Arab media as a “War against Islam”. An analysis theorizes that the popularity of conspiracy theories in the Arab world is “the ultimate refuge of the powerless“. And Al-Mumin Said, head of the Al-Ahram Research Center in Egypt, noted the danger of such theories in that they “keep us not only from the truth but also from confronting our faults and problems …”

On the political level in newer times, conspiracy theories started to gain traction in the Arab world with the 1967 Six-Day War, resulting in a decisive Arab defeat,. The war was perceived as a conspiracy by Israel and the United States—or its opposite: a Soviet plot to bring Egypt into the Soviet sphere of influence. Numerous conspiracy theories “were usually the most implausible, wild-eyed conspiracy theories one could imagine … Israelis, the Syrians, the Americans, the Soviets, or Henry Kissinger—anyone but the Lebanese—in the most elaborate plots to disrupt Lebanon’s naturally tranquil state.”

In early 2020, according to Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) reports, there have been numerous reports in the Arab press that accused the US and Israel of being behind the creation and spread of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic as part of an economic and psychological war against China. One report in the Saudi daily newspaper Al-Watan claimed that it was no coincidence that the coronavirus was absent from the US and Israel. The US and Israel have also been accused of creating and spreading other diseases, including Ebola, Zika, SARS, avian flu and swine flu, through anthrax and mad cow disease.

But it is not always politics triggering conspiracy theories: A common one is about soft drink brands Coca-Cola and Pepsi, that the drinks deliberately contain pork and alcohol and their names carry pro-Israel and anti-Islamic messages.

Using fake news as a political tool for Putin’s new „world order“

When Russia’s war in Ukraine began, Facebook, Twitter and other social media giants moved to block or limit the reach of the accounts of the Kremlin’s propaganda machine in the West. The effort, though, has been limited by geography and language, creating a patchwork of restrictions rather than a blanket ban, ignoring the increasing use of those networks in Arab-speaking communities.

There, a steady stream of Russian propaganda and disinformation continues to try to justify Putin’s invasion, demonizing Ukraine and obfuscating responsibility for Russian atrocities that have killed thousands of civilians.

The result has been a geographical and cultural asymmetry in the information war over Ukraine that has helped undercut American- and European-led efforts to put broad international pressure on Mr. Putin to call off his war.

And the failure of Facebook, Twitter and TikTok, the Chinese-owned app, to impose stronger checks on Russian posts in Arabic, but also Turkish languages has begun to draw criticism as the war drags on. While EU and US officials have banned content from the Russian-state-owned media outlets Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik across the European Union and the US, one main target for Russia’ propaganda experts reached out to Arab networks.

As the role of social media keeps growing in the region, the Middle Eastern cyberspace beckons the Kremlin to expand its informational outreach. With fake reporting on social media platforms for news in Arabic it enables Moscow to reach millions, not only in the region itself, but also in Western countries with high numbers of Arab-speaking minorities. RT and Sputnik Arabic produce significantly more content on Twitter than BBC Arabic or Al Jazeera. While RT Arabic and Sputnik Arabic have been posting a daily average of 180 and 87 tweets respectively since their creation, Al Jazeera maintains an average of 55 tweets and BBC Arabic a mere 32. In general, RT and Sputnik emphasize that the U.S. and its European allies are responsible for the instability in the Middle East while cultivating Moscow’s image as a stabilizing force. Given the resentment felt by many in the Middle East about the West’s misadventures in the region, this narrative naturally resonates.

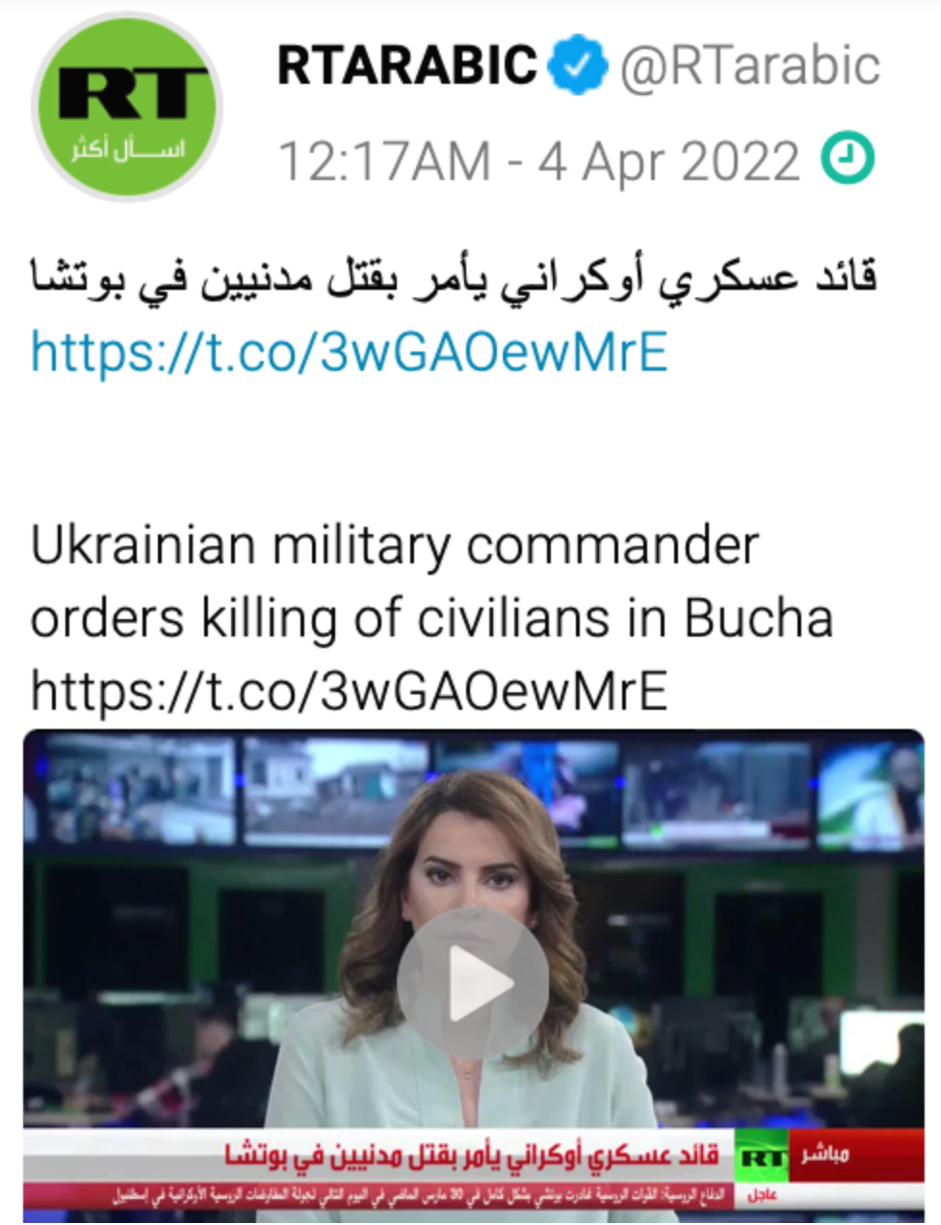

Over the past months, the daily post frequency of the RT Arabic and Sputnik Arabic has increased significantly on Twitter (by 35% and 80% respectively). According to a TruthNest analysis, three out of the six most popular tweets by RT Arabic amplified conspiracies spread by the Russian Ministry of Defense about secret biological laboratories developed by the US in Ukraine. The third most popular tweet was a video claiming that a Ukrainian military commander had ordered the massacre of civilians in Bucha, followed by a video blaming NATO for the current war between Russia and Ukraine and arguing that Moscow was working to avoid a “world war scenario.” Both RT and Sputnik Arabic refer to Russia’s actions in Ukraine as a “special military operation” (“العملية-العسكرية-الخاصة”), as the terms “war” and “invasion” continue to be banned by the Russian state.

On Twitter, for example, merely typing “Ukraine” in Arabic yields a slew of overwhelmingly pro-Russian messaging. There is a tweet of a video of a hospital bombing Russia committed in Mariupol with devastating consequences for civilians. This tweet directs the reader to a video of Mosul in 2016, when the US targeted a hospital being used as an ISIS operations center in the battle to retake Mosul from ISIS control. According to the tweet though, the context is somewhat different. It reads: “the so-called humanity of Obama in Iraq as he bombed a hospital in Mosul with internationally banned chemical weapons. This is how the children of Mosul were buried.”

Today, young Arabic speakers are flooded with anti-democratic messages around the clock. They are inescapable, particularly on social media. Those who attempt to educate their peers on civic engagement on social media face formidable challenges, while fake news and conspiracy theories, conducted by authoritarian regimes like Russia are dominating the narrative. The question we must ask ourselves is, what is the truth worth to us?

All publishing rights and copyrights reserved to MENA Research and Study Center.