Almost half of the Muslims living in Europe believe that there is only one valid interpretation of the Quran, that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam and that religious laws are more important than secular ones. Using these indicators, a study by the Science Center Berlin (WZB) shows in six countries that religious fundamentalism is much more widespread among Muslims than among Christians. The finding is worrying insofar as religious fundamentalism is associated with an increased level of xenophobia.

During the heated controversies over immigration, terrorism and Islam, Muslims have been widely associated in the public eye with religious fundamentalism. Some have argued against this as religious fundamentalism can only be found among a small minority of Muslims living in the West and can also be found among adherents of other religions, including Christianity. But the claims of both sides lack a solid empirical basis. Little is known about the spread of religious fundamentalism among Muslim immigrants. There is practically no meaningful data that allows a comparison with native Christians.

The WZB study on immigrants and natives in six European countries – Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria and Sweden – provides for the first time a solid empirical basis for answering these questions. 9,000 people with a Turkish or Moroccan migration background and a local comparison group were interviewed. Religious fundamentalism can be defined in science in terms of three key elements:

- Believers should abide by the eternal and immutable rules set forth in the past have.

- These rules allow only one interpretation and are for all believers binding.

- Religious rules take precedence over secular laws.

These aspects of fundamentalism were measured by the following statements, presented to local people who identified themselves as Christian (representing 70 percent of the local people surveyed) and respondents of Turkish and Moroccan origin, of whom 96 percent identified themselves as Muslim:

- “Christians/Muslims should return to the roots of Christianity/Islam.”

- “There is only one interpretation of the Bible/Quran and all Christians/Muslims must adhere to it.”

- “The rules of the Bible/Quran are more important to me than the laws of the country I live in.”

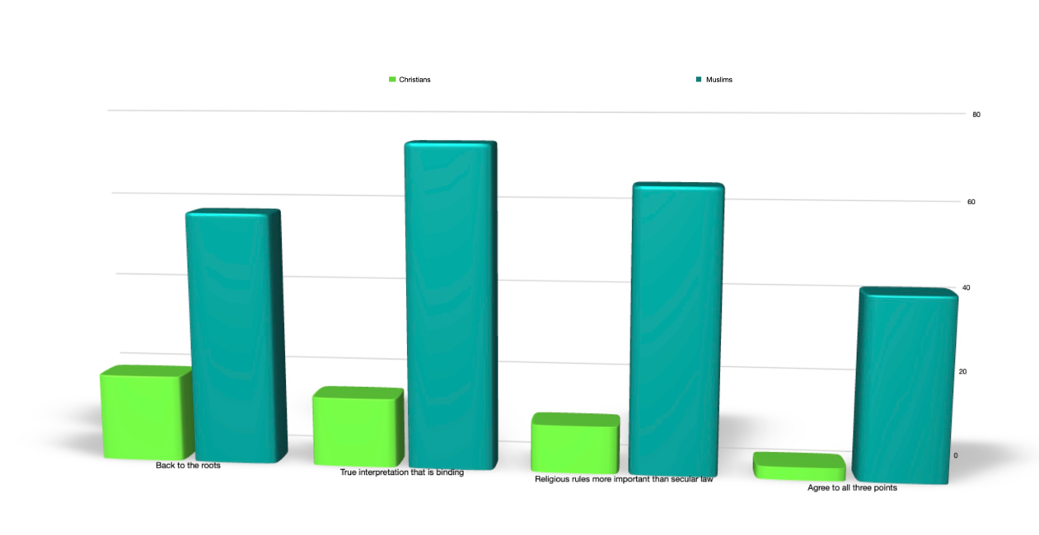

The chart shows that religious fundamentalism is not a marginal phenomenon in Western European Muslim communities. Almost 60 percent agree that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam. 75 percent believe that there is only one interpretation of the Quran that all Muslims should adhere to and 65 percent say that religious rules are more important to them than the laws of the country in which they live. 44 percent of the Muslims surveyed have consistently fundamentalist convictions and agree with all three statements. Fundamentalist attitudes are somewhat less common among Sunni Muslims with a Turkish background (45 percent agreeing with all three statements) than among those with a Moroccan background (50 percent). Fundamentalist beliefs are much less common among Alevis, a minority Turkish faith within Islam (15 percent).

The chart shows that religious fundamentalism is not a marginal phenomenon in Western European Muslim communities. Almost 60 percent agree that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam. 75 percent believe that there is only one interpretation of the Quran that all Muslims should adhere to and 65 percent say that religious rules are more important to them than the laws of the country in which they live. 44 percent of the Muslims surveyed have consistently fundamentalist convictions and agree with all three statements. Fundamentalist attitudes are somewhat less common among Sunni Muslims with a Turkish background (45 percent agreeing with all three statements) than among those with a Moroccan background (50 percent). Fundamentalist beliefs are much less common among Alevis, a minority Turkish faith within Islam (15 percent).

Contrary to the assumption that fundamentalism is a reaction to exclusion by the host country. But even among German Muslims, fundamentalist views are widespread: 30 percent of respondents agree with all three statements. Comparisons with other German studies show remarkably similar results. In the study “Muslims in Germany”, 47 percent of the German Muslims surveyed agreed that following the rules of their own religion was more important than democracy, just as many as the proportion of those in our study who believed that the rules of the Quran are more important than German laws.

Another notable finding is that religious fundamentalism is much more widespread among Muslims than among native Christians. Between 13 and 21 percent of Christians agree with each statement, and less than 4 percent can be characterized as consistent fundamentalists because they agree with all three statements. Consistent with what we know about Christian fundamentalism, agreement with these statements is slightly higher among mainstream Protestants (4 percent agree with all statements) than among Catholics (3 percent) and highest (12 percent) among adherents of smaller Protestant groups. But even among these groups, support for fundamentalism is far less than among Sunni Muslims. The Turkish Alevis’ view of the role of religion, on the other hand, resembles that of the native Christians much more closely than that of the Sunni Muslims.

Given that the demographic and socio-economic profiles of Muslim immigrants and native Christians are very different, and given that it is known from the literature that marginalized, lower-class people are more attracted to fundamentalist movements, it would of course be possible that these differences have an impact on the social class and not due to religion. A cause for concern is the fact that fundamentalist attitudes are as common among young Muslims as among older ones, while they are much less common among young Christians than among older Christians.

Research on Christian fundamentalism in the US has revealed a strong hostility towards other groups seen as a threat to the religious in-group. To what extent is this connection also found in the European context? Three questions help here:

- “I don’t want to have homosexual friends.”

- “You can’t trust Jews.”

- “Muslims want to destroy Western culture.”/”Western countries want to destroy Islam.”

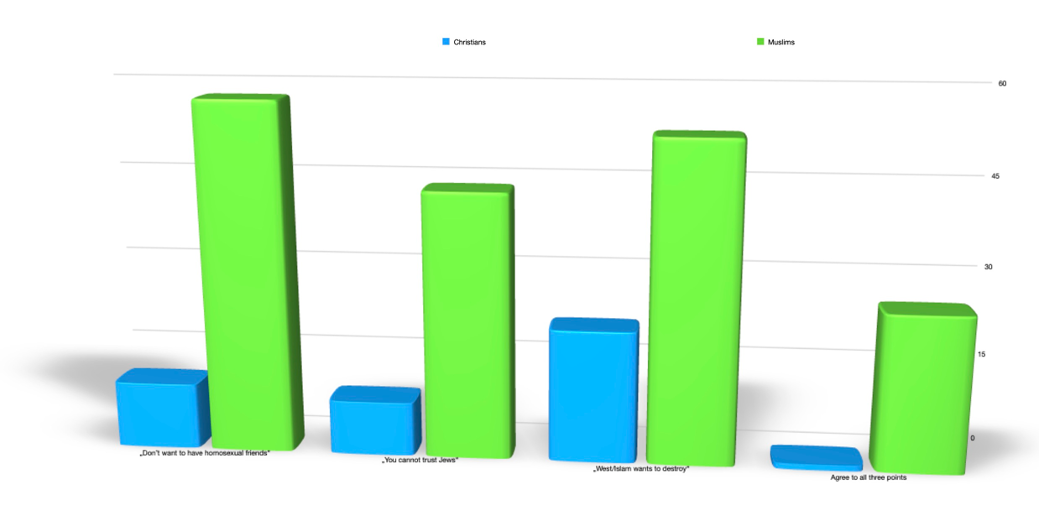

This shows that hostility towards strangers among native Christians is by no means negligible. As many as 9 percent are openly anti-Semitic and agree that Jews cannot be trusted. In Germany, this percentage is even higher (11 percent). A similar number reject homosexuals as friends (13 percent on average in all countries, 10 percent in Germany). Unsurprisingly, Muslims are the out-group that generates the highest level of hostility: 23 percent of native Christians (17 percent in Germany) believe that Muslims want to destroy Western culture. Few native Christians are hostile to all three groups (1.6 percent). If we consider all locals and not just Christians, the level of xenophobia is slightly lower (8 percent against Jews, 10 percent against homosexuals, 21 percent against Muslims, and 1.4 percent against all three).

This shows that hostility towards strangers among native Christians is by no means negligible. As many as 9 percent are openly anti-Semitic and agree that Jews cannot be trusted. In Germany, this percentage is even higher (11 percent). A similar number reject homosexuals as friends (13 percent on average in all countries, 10 percent in Germany). Unsurprisingly, Muslims are the out-group that generates the highest level of hostility: 23 percent of native Christians (17 percent in Germany) believe that Muslims want to destroy Western culture. Few native Christians are hostile to all three groups (1.6 percent). If we consider all locals and not just Christians, the level of xenophobia is slightly lower (8 percent against Jews, 10 percent against homosexuals, 21 percent against Muslims, and 1.4 percent against all three).

These numbers are troubling enough for natives, but they are far dwarfed by the level of out-group hostility among European Muslims. Almost 60 percent disapprove of homosexuals as friends, and 45 percent think that Jews cannot be trusted. While about one in five natives can be considered Islamophobic, the level of phobia against the West – which curiously has no word, you could call it “occidental phobia” – is much higher among Muslims: 45 percent believe the West wants to destroy Islam. These results are consistent with a Pew Research Center study showing that about half of Muslims in France, Germany and the UK believe the 9/11 attacks were not perpetrated by Muslims but were planned by the West and/or Jews became.

A good quarter of Muslims show hostility towards all three out-groups. In contrast to the results on religious fundamentalism, out-group hostility is more widespread among Muslims of Turkish origin (30 percent agree with all three statements) than among Muslims of Moroccan origin (17 percent). Among Alevis (13 percent agree with all three statements), the level of out-group hostility is much lower than among Sunni Muslims of Turkish origin (31 percent), but the difference is smaller than for religious fundamentalism. A worrying aspect is the fact that out-group hostility is not significantly lower among young Muslims than among older Muslims, while among native Christians the generation gap is considerable.

Again, it is important to ensure that differences between Muslims and natives are not due to the different demographic and socio-economic makeup of these groups, as xenophobia is known to be higher among socially disadvantaged groups. In addition, the group differences are much larger than the socioeconomic differences. For example, the difference in xenophobia between those with a low level of education and those with a university degree is about half that between Muslims and native Christians.

If we include religious fundamentalism, it turns out to be by far the most important sign of out-group hostility and explains most of the differences in levels of out-group hostility between Muslims and Christians. The greater out-group hostility among Sunnis of Turkish origin compared to the Alevis can also be explained almost exclusively by the higher level of religious fundamentalism among the Sunnis. Religious fundamentalism not only explains why Muslim immigrants are generally more hostile to out-groups than native Christians, but also why some Christians and some Muslims are more xenophobic than others.

These findings clearly contradict the often-heard claim that Islamic religious fundamentalism in Western Europe is a marginal phenomenon or its extent is no different from fundamentalism among Christians. Both claims are obviously false, with nearly half of European Muslims agreeing that Muslims should return to the roots of Islam, that there is only one interpretation of the Quran, and that the rules laid down in the Quran are more important than secular laws. Not even every 25th of the native Christians can be described as fundamentalist in this sense. Moreover, religious fundamentalism is not an innocent form of strict religiosity, as evidenced by its close relationship with out-group hostility, both among Christians and Muslims.

The extent of Islamic religious fundamentalism, as well as its correlates —homophobia, anti-Semitism, and “occidental phobia” — should be of serious concern to policymakers and Muslim community leaders alike. Of course, religious fundamentalism should not be equated with a willingness to support or even take part in religiously motivated violence. But given its strong relationship with out-group hostility, it is very likely to provide a breeding ground for radicalization. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that Muslims are a relatively small minority in Western Europe. While relative levels of fundamentalism and out-group hostility among Muslims are much higher, in absolute terms there are at least as many Christian fundamentalists as Muslim fundamentalists in Western Europe, and the vast majority of homophobics and anti-Semites remain local.

All publishing rights and copyrights reserved to MENA Research and Study Center.