The Turkish general election will be held on 18 June 2023. The elections will determine the next president and the government in a fragile environment. After being in power for two decades, Erdogan faces the most challenging election since he significantly lost his popularity, notably due to the plunging economy and high inflation, which officially stands at 83.45%. The calculated rate is said by independent analysts to be around 186%. The stark contrast does exhibit itself not only in financial figures. Turkey became “the world’s biggest jailer of journalists”, according to PEN International and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ),” and it is considered “not free,” according to the Freedom House index with a score of 32.

Various polls indicate that the opposition has a good chance of defeating Erdogan, which gives a glimpse of hope to tired Turkish citizens and outsiders alike. It is a good thing to have hope. Yet, excessive hope generates disillusions and prevents a healthy analysis of the current situation. Planning the future just upon wishful thinking poses a grave danger.

Most commentators fail to grasp the extent to which 2023 polls are not just elections per se but a matter of survival for Erdogan, who is beyond dispute the most powerful man in today’s Turkey. Erdogan acquired this power by profoundly engineering the Turkish state and society and building a unique toolkit to solidify his position. Without understanding this far-reaching transformation and the assets at his disposal, it makes no sense to analyse Turkey’s future. In this article, I will scrutinise how Erdogan transformed the Turkish state and society and unpack what kind of domestic tools are at his disposal that can be used in the 2023 elections by looking into the previous examples. The analyses here will be complemented in a second article, where I will address the means that he can employ outside Turkey, such as triggering a crisis or war in order to invoke a state of emergency or cancel elections and exploiting the European citizens with Turkish origins to deter other countries from promoting democracy in Turkey. Lastly, I will analyse the implications of this election for Turkey and the EU.

- The road to today’s environment: How did Erdogan design the Turkish state and society?

Erdogan indicated that his third term following the 2011 general elections would be his mastery period which heralds a new era. In 2013, he suffered from two significant events; Gezi Park Protests and the 17/25 December Corruption Scandals. Both events show important similarities concerning Erdogan’s reaction. He considered both events a coup plot against himself and brutally responded to them. During Gezi Protests, approximately 7500 people were wounded, and strikingly the mainstream media disregarded the protests and continued to their standard schedule of broadcasting penguin documentaries. Following the corruption scandal, Erdogan sacked thousands of police officers and changed prosecutors and judges.

These shocking events taught Erdogan the power of social media. In 2014, Twitter was banned for a few weeks after he stated: “we will eradicate Twitter and all of them. I don’t care about what the international community says.” At the same time, AK Party created an army of 6000 social media trolls from scratch. The number has increased over time, and according to a statement by a senior leader of Osmanli Ocaklari, which is described as a “pro-government paramilitary organisation” by the Dutch National Security and Counter-Terrorism Coordinatorship (NCTV), this number increased to 200 000 people in 2023.

After the 17/25 corruption scandal, Erdogan and his inner circle were badly busted with serious evidence. Moreover, Reza Zarrab, the man who is the central figure in the investigation, pleaded guilty in the US and provided all evidence to the American courts. Therefore, the world knows his criminal network, and there is no way to deny accusations.

As a result, Erdogan started to transform the media, judiciary, police department, as well as other state institutions except for the Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) until 2016. Erdogan would deal with the latter or the latest obstacle in this transformation after the so-called 15 July coup attempt in Turkey, which he called “a gift from God.” The coup was full of irregularities, notably its occurrence time early in the evening, unlike the previous examples in the country with a rich institutional memory of coups.

Critics described the coup as a “controlled coup,” a false flag operation, Turkey’s Reichstag Fire, a counter-coup or “a self-coup,” a term that caused Erdogan’s regime to ban Wikipedia. Erdogan could not convince the international community, Western intelligence agencies, and even his son-in-law, who was laughing in front of the cameras while he furiously talked about the coup attempt.

Despite the profound flaws, the results were exactly what Erdogan badly needed to establish his regime and bring the presidential system. As Martin Schulz, the former president of the European Parliament, pointed out: “the coup was not well-prepared at all, but the response was meticulously drawn up.”

In the aftermath of the coup, thousands of judges, prosecutors, teachers, and even a baklava seller were arrested on suspicion of being a member of a terrorist organisation. Hundreds of media outlets, associations, foundations, private hospitals, and educational establishments were shut down by decrees, and their assets were confiscated without compensation.

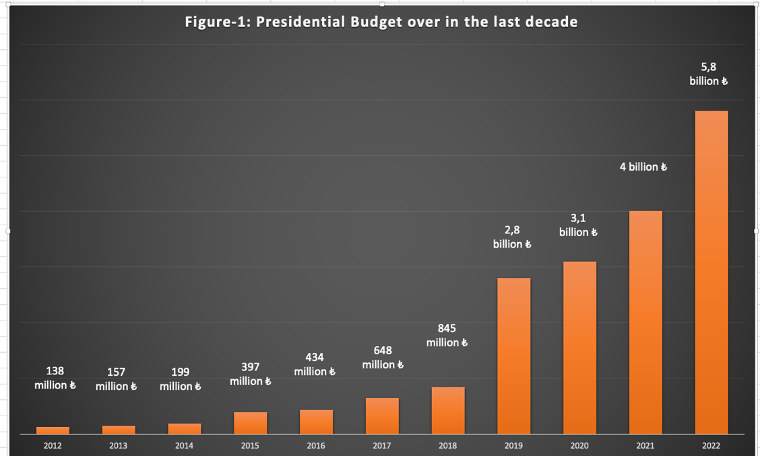

Erdogan already had strived to have a presidential system in which all power is given to him as the president, and he succeeded in this objective. Following the controversial constitutional change in 2017, he connected many state institutions to himself. For this massive reorganisation, he built the third biggest palace in the world, which is 30 times bigger than the White House, established secretaries within this complex, and massively increased budgets, especially for the critical institutions. The most notable changes took place in the presidency, national intelligence (MİT), the presidency of religious affairs (Diyanet) and the military. These are no longer independent organisations but an embedded part of a super-powered president.

The second most significant transformation was in the Turkish Armed Forces and security bureaucracy. He carried out a massive purge from high-level generals to low-level military officers and petty officers. The military schools were closed, all cadets were fired, and they were replaced with loyal people chosen from his party members, religious sects close to him, and associations funded and managed by his close circle and his son, notably TUGVA.

The second most significant transformation was in the Turkish Armed Forces and security bureaucracy. He carried out a massive purge from high-level generals to low-level military officers and petty officers. The military schools were closed, all cadets were fired, and they were replaced with loyal people chosen from his party members, religious sects close to him, and associations funded and managed by his close circle and his son, notably TUGVA.

The interviews during the recruitment to the military schools were also conducted by SADAT, Erdogan’s parallel and private army, similar to Putin’s Wagner Group, or revolutionary guard in Iran. The same organisation took a role in training and transferring jihadists to Libya, Karabagh, and other MENA states in collaboration with the Turkish Intelligence (MİT), which is documented by the US Department of Defense, Israel and the United Nations.

He restructured the military and appointed Hulusi Akar as the minister of defence, who failed to give necessary orders as the military chief at the time of the coup. Though he is a minister, Akar acts like a commander-in-chief and even wears a special military uniform with ranks, particularly in military ceremonies and conducts visits to different military bases. As a result, they planned every recruitment and appointment in each corner of the country at every level and transformed Turkey completely into a party state.

Erdogan changed Turkey’s long-standing foreign policy orientation from the West to the East and pursued an aggressive foreign policy. A few months after the coup, the high-level military officers were purged, and he started the first incursion into Syria, a moving subject of serious critique by the security bureaucracy, notably the generals in the army. Since then, Turkey has been involved in many conflicts and crises from Libya to the Caucasus and has become a regional troublemaker. Erdogan’s new armed forces even facilitated oil trade with ISIS and or treated ISIS fighters in Turkish hospitals. The procurement of the S-400 became a salient manifestation of this reorientation and caused Turkey’s removal of the F-35 programme and implement the US sanctions under CAATSA.

The police department had already been reshuffled many times since the 17/25 corruption cases. After 15 July, the purge continued. As one police officer who was responsible for detaining soldiers told me on the condition of anonymity: In the morning, we left the police station to arrest people. In the evening, we arrested our colleagues whom we detained soldiers in the morning.

For Erdogan’s paranoia, this transformation was not enough. In addition to creating a private army, he also formed pro-government militias by arming civilians and rekindling the watchmen in 2016, a disbanded police branch in 2008 and known as Bekçi in Turkish. Educated in just 60 days, 21000 men were granted extensive powers such as carrying weapons and searching suspects in 2020.

Moreover, the ministry of internal affairs was left to a controversial figure, Suleyman Soylu, who has pictures with many gang and mafia leaders and allegedly became a drug kingpin. Erdogan and his associates are currently also being accused of drug trafficking.

Until now, it evidently seems that the security apparatus in Turkey and the parallel structures will only be loyal to Erdogan in case of his loss, not to the constitution.

- What kind of tools did Erdogan use in the previous elections?

There have been widespread fraud allegations in the elections in Turkey as early as 2014. In the elections this year, electricity blackouts happened in the regions with slim margins. The energy minister at the time blamed a cat walking into a transformer unit.

In 2017, Supreme Election Council made an unprecedented decision despite the laws dictating otherwise that unstamped ballots would be counted. This decision ignited widespread protests around Turkey, and some protesters were arrested. In 2018, the Turkish government passed a law that unstamped ballots would be regarded as valid, undermining efforts to prevent fraud during the elections.

The 2018 presidential elections, which Erdogan prepared meticulously in the last years, were held before its usual time, and the elections took place 5 months earlier. Turkey entered the election atmosphere in a state of emergency, and the US, the EU, and the UN voiced their concerns about transparent, fair, and free elections.

Selahattin Demirtas, the co-chair of the Kurdish party HDP, was imprisoned by Erdogan and had to carry out his campaign from his prison by delivering his messages to the lawyers, not directly to any media outlets. Two days before the election, fake leaflets were created in Ankara on behalf of opposition parties, but interestingly it could not be identified who prepared or distributed them.

Heavy censorship existed against the opposition in the state and mainstream media. For instance, state broadcaster TRT allocated 37 hours for Erdogan and his ally, whereas the combination of opposition parties could only find coverage for less than 4 hours. It was also noteworthy that the pro-government TVNET channel suddenly broadcast election results from the Anadolu Agency (AA) with the vote rates written on it four days before the elections. Followingly, they stated that this was a test broadcast and denied other allegations.

During these elections, there had been evidence and videos about fraud, such as indicating polling station staff who cast empty ballots for Erdogan, stolen ballots, excess votes per box, and invalid ballots.

In the 2019 municipality elections, when Erdogan’s party lost the election to the opposition candidate Ekrem Imamoglu, who is sentenced by Erdogan’s regime today, Supreme Election Council decided to repeat only city elections but to keep the results of the local elections, which were cast on the same ballots. Strikingly, data flow from the Supreme Election Council to the opposition parties and from Anadolu Agency to the TV Channels was disrupted.

Despite these irregularities and the power Erdogan’s party has within the state, he claimed that the opposition stole the ballots and conducted organised fraud in the elections. In the second round, Imamoglu outscored 10% against Erdogan’s candidate.

Turkey faced many irregularities and elections in the last decade. Judiciary branches overseeing this process made controversial decisions in favour of Erdogan. Heavy censorship, along with disruptions and manipulations in the data flow, as well as electricity blackouts, often occurred.

Considering the fact that Erdogan already controls the judiciary and the security forces in the country and that once parting from the government, the illegal things he and his immediate circles committed will come out, it would not be a prophecy to know that he would use every tool at his disposal not to lose the elections.

In the following article, I will dive deeper into assets that Erdogan can employ abroad and the implications of the elections for Turkey and Europe.

All publishing rights and copyrights reserved to MENA Research and Study Center.