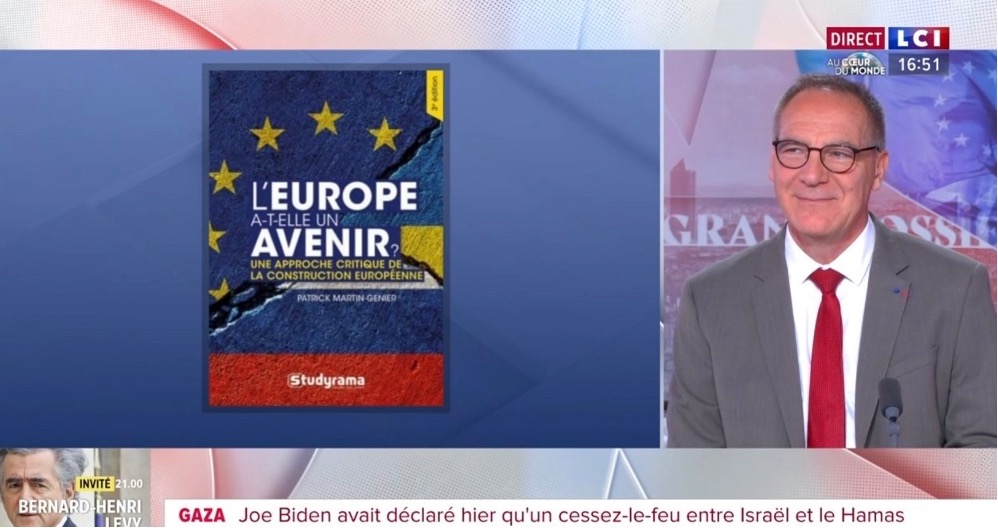

Patrick Martin Genier, lecturer at Sciences Po, specialist in European and international issues, author of “L’Europe a-t-elle un avenir” (StudyRama). The interview was conducted on 10 May 2024 by Denys Kolesnyk, a French consultant and analyst based in Paris.

Yesterday, the United States threatened Israel with stopping arms deliveries if the Israelis continued their operation in Rafah. How can you explain this move, especially given that the United States is Israel’s most important supporter, and has even redirected the delivery of shells to Israel after the Hamas attack, to the detriment of Ukraine?

_I think it is rather _a limited warning than a threat. The United States does not want Israel and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to carry out an offensive on Rafah, because they started from the principle that they agreed to eliminate the Hamas terrorist movement, but the fact remains that since the start of this offensive, the damage has been done mainly to the civilian population.

Secondly, it was clear that this conflict had set our Western societies, particularly American ones, ablaze. We have seen it on university campuses at Columbia, the University of Los Angeles, and other American universities, as well as at Sciences Po in Paris and in the French provinces. It’s clear that there’s a kind of conflagration. And, of course, Joe Biden is campaigning for re-election as President of the United States, and the Democratic electorate is very much in favor of ending the war, or at least achieving a ceasefire.

So, Biden is under international pressure, and he is under pressure from his electorate and his constituents. This has led him to threaten, as you say, Israel to stop any offensive on Rafah. If Israel does not comply, he may suspend the delivery of shells, which would not necessarily be effective with regard to Rafah.

You just mentioned that there were also demonstrations at Sciences Po in Paris. What is France’s position in all this? Especially given that in the past, even in the twentieth century, France was a fairly important player in the Middle East.

Historically, since General de Gaulle, France has always maintained a balanced position in the Middle East. Firstly, France is an unwavering supporter of Israel, and our successive presidents have always visited Tel Aviv. French presidents, notably François Mitterrand, have addressed the Israeli parliament, the Knesset.

However, France has also consistently supported the creation of a Palestinian state. Paris has always had cordial relations with the head of the Palestinian Authority, particularly Yasser Arafat. Our country has always campaigned for the creation of two states, with at least one living peacefully alongside Israel. France has always supported the Palestinian cause.

Thus, the challenge for French diplomacy is to strike a balance between these two commitments: Israel’s security, which has always been strongly supported, and the creation of a Palestinian state.

This balanced position in the Middle East has not always been understood, particularly under the current president, Emmanuel Macron. On the one hand, we offer unwavering support for Israel, but on the other hand, we have become very critical of this country, like the stance of the Left side of the political spectrum. Therefore, while we maintain strong support for Israel, we also hold positions that have raised some questions, particularly in relation to Germany, which is itself an unwavering supporter of Israel.

In other words, our balanced position has not always been understood, _nevertheless it has always been the stance of French diplomacy in the Middle East.

In Western countries, in democracies, public opinion plays an important role. In your opinion, what influence do minorities, particularly North African and Muslim minorities, have in shaping France’s position on certain international crises? Do we also have our own ‘Arab street’ to contend with?

_As you know, in all democracies, we naturally pay particular attention to the electorate. This is also perfectly normal for the United States.

As for France, we have a historic tradition with special ties to the Sahel and the “Arab world”, since we had our colonies in these areas. We have special agreements with these countries, particularly on immigration, and we have agreements with Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. Beyond North Africa, we also have agreements with French-speaking Africa, because the French-speaking world is very important to France.

We always pay attention to this particular electorate. France, which is a secular country, takes great care to maintain relations with the various religious denominations, and the Ministry of the Interior is responsible for it. _Thus, beyond this freedom of religious expression, France naturally needs to have balanced relations with the various Arab countries, but this is not always easy.

However, I wouldn’t go so far as to say that minorities play a role in our foreign policy. I would rather say that France always tries to have this balanced diplomacy, with respect for all religious and ethnic communities. But this is not a determining factor in the conduct of French diplomacy. Finally, once again, France has never failed to support Israel.

I would like to stress that we must make a clear distinction between the importance of minorities and the conduct of international diplomacy, as well as the interests of the state. The interests of the state are guided by our history, but also by the need to control immigration.

As you know, Israel eliminated a number of Iranian generals in Syria with a strike on an Iranian diplomatic compound. The Iranians retaliated, and this was the first time they had retaliated directly with strikes on Israeli soil. The West supported Israel and shot down many of the missiles and drones. How do you explain the fact that Iran dared to strike Israel directly?

Indeed, the game was always played _before via proxies and by applying the principle of plausible deniability, in other words: “it’s us, but it’s not us”.

_Furthermore, I believe that fundamentally it is not a change of approach, but a change of strategy. There is a debate within the mullahs’ regime, which is a bloodthirsty dictatorship. And there is competition between the different factions in Tehran.

It seems that there was this desire to retaliate, which was a demand from the most radical faction. It should be noted that this was not the first time that Israel had struck at targets and eliminated Iranian high-ranking officers, but here the difference was that it was a strike on an Iranian consular compound in Syria, where the General of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, commander of the Al-Quds force in Lebanon and Syria, Mohammad Reza Zahedi, had made his centre of terrorist activities.

Thus, the fact that a diplomatic institution was hit may well have led to this temporary change of strategy and prompted the Tehran regime to strike directly at Israel. As a result, the regime felt obliged to carry out these strikes. I believe that, ideologically, militarily and politically, the hardest factions prevailed and the Mullahs’ regime was obliged to strike back.

Indeed, it was a necessary response, but they went on to say that it was a one-off and would not be repeated. Indeed, as you mentioned, until now Iran has used its proxies, the three “H”: Hezbollah, Hamas and the Houthis, to carry out its actions. These groups are effectively Iran’s agents, even if some say that they do not always obey Tehran’s orders. The fact remains that Hezbollah represents a real threat to Israel, often acting on its behalf.

However, the attack on a consular institution created an obligation for Iran to intervene directly. So, Iran has shown through these strikes that it represents a real danger to Israel’s very existence.

And you have just mentioned the three ‘H’s: the Houthis, Hezbollah, and Hamas, and there is a proliferation of conflicts in the Middle East at the moment. The Houthis de facto control almost all of Yemen and are causing major disruption to shipping. But so far, American and British strikes have not been effective. So, in your opinion, is Iran really behind their activities, or do the Houthis act solo? Or is it a question of aligning interests? And secondly, how can we resolve this crisis?

It’s a big problem, a difficult question, indeed. At first, I was convinced that a few bombing raids on areas controlled by the Houthis would resolve the situation. However, this is clearly not the case. The Houthis are well established and control a large part of the country, particularly the mountainous areas, in opposition to the official authorities.

As far as I’m concerned, there’s no doubt that they also take their orders from Iran and serve the same interests. They have even targeted ships going to Israel, which is a real danger. By disrupting maritime traffic, they are serving the objectives of Iran, which is seeking to exert direct pressure on Israel.

Given that maritime traffic in the Red Sea accounts for a significant proportion of world trade, the Western powers, in particular the United States, the United Kingdom and France, cannot afford to allow this kind of terrorist action to continue. They have every interest in countering these disruptions to maintain the security of this crucial maritime route.

So, although the Houthis have their own interests, they share common goals with Iran, which is seeking to destabilise global shipping. Western strikes, while important, have had a very limited impact.

And this is where international diplomacy can perhaps play a role. Unofficial contacts with the United States, of course, but also with other powers such as China, which does not necessarily have an interest in seeing traffic disrupted in this part of the Red Sea. Indeed, China, with its own New Silk Road that passes through there, as well as countries like Japan and India, have no interest in seeing maritime traffic seriously disrupted. And given the ineffectiveness of Western bombing, diplomacy could play a crucial role.

Indeed, we have seen that China has tried, to some extent, to convince or at least talk to Iran asking to influence the Houthis in Yemen to stop disrupting shipping. However, these efforts have not yielded results. The question remains: to what extent can diplomatic means really influence Iran? And how far can we really influence Iran?

That’s another important question. Even if China is not really an ally of Iran, it is one of the powers challenging the Western order. However, either it has not found the arguments necessary to influence Iran, or Iran does not have enough influence over the Houthis, which brings us back to the previous question.

There are sometimes unknowns and unresolved equations in this part of the world. What we do know is that China is challenging the world order and seeking to play a significant role on the international stage, particularly in the Middle East. It is not entirely aligned with Russia and wants to go its own way, as demonstrated by its growing involvement in Africa.

Recently, an event that went largely unnoticed took place: a Hamas delegation was received in Beijing by the Chinese deputy foreign minister, in an attempt to reconcile Hamas and Fatah. This clearly shows that China is conducting independent diplomacy and, in exchange for investment and funding, could potentially exert influence on Iran. For the moment, this influence is not yet fully effective, and Chinese diplomacy still seems to be groping its way along.

This can also be seen in the preparations for the international conference on Ukraine scheduled for next month, where Chinese proposals were reiterated this week by Xi Jinping during his visit to Hungary. The Hungarian leader said that he was counting heavily on China’s proposals for peace in Ukraine. So, China is present on the international stage, but it remains to be seen whether its initiatives will be crowned with success.

Let’s talk about the interests of foreign powers in the region. Despite announcements of troop withdrawals, the United States has maintained a significant presence since its invasion of Iraq in 2003. Russia, after a period of relative inactivity following the USSR’s dissolution, has returned forcefully in Syria. Iran is also playing a major role, and China, despite having only one military base in Djibouti, is seeking to increase its influence. In your opinion, what are the interests and motivations of these powers in the region?

The situation as I see it is a game being played by the major powers, a challenge to American power in the region. We can see the power games being played, for example with Saudi Arabia, but in reality everyone is playing their own game, advancing their own pawns.

It is well known that Saudi Arabia aspires to become a major player in the region. Riyadh has supported Israel’s rapprochement with certain Middle Eastern countries through the Abraham Accords. But to establish itself as a regional leader, in direct competition with other regimes such as Iran, which is a bloodthirsty dictatorial regime, and Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, which is a pariah among nations, but which is gradually re-entering the concert of nations in this region, because we have not managed to dislodge him.

The United States, for its part, is seeking to protect its interests. Under the Trump administration, it has adopted an extremely offensive stance with the Abraham Accords, but this diplomacy has borne fruit, contrary to what many say. The only major problem is that the issue of Palestinian state has not been resolved, which could be seen as a flaw in these agreements. Washington wants to continue to play a major role, because once a major power withdraws, that country loses considerable weight.

As far as Russia is concerned, it is clear that Vladimir Putin, who has been in power for over 20 years and wishes to remain in power until 2036, is seeking to reconstitute the influence of the Soviet empire. The Soviet Union has always played an important role and maintained privileged relations with the regimes of the Middle East, and this is not changing. Putin actively supports Bashar al-Assad in Syria and other dictatorships in the region. He has also welcomed Iranian leaders to Moscow with great fanfare.

Russian diplomacy thus appears to be a continuation of Soviet diplomacy, with the aim of reconstituting its empire and maintaining a strong influence in the Middle East.

As for China, this is something rather new. Beijing is demonstrating that it has become stronger militarily, with its weapons getting more powerful. It also seems intent on continuing to develop its nuclear arsenal, thus demonstrating its imperialist aspirations. This is especially clear in places like the South China Sea, the Sea of Japan and regarding Taiwan.

As a major power, China has considerable financial resources at its disposal to invest abroad. When it enters a country, it does not limit itself to diplomatic influence, but also offers investment in infrastructure, and this is also the case in the Middle East.

So, there is a game involving three major powers seeking to extend their influence in this region, bearing in mind that, for example, Vladimir Putin went to Turkey to propose the installation of nuclear power plants.

Beyond the Middle East, this struggle for influence extends to Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, as we have seen in the Sahel countries with the Prigozhin involvement. China, for its part, offers turnkey solutions. I have met Africans who have told me: “The Chinese build a factory, they bring their own staff, they make fewer speeches but they are more efficient”.

It is therefore clear that there is a confrontation between these three great powers, with the Middle East as the main battleground, but also an extension of this rivalry into sub-Saharan Africa.

And finally, in your opinion, are we seeing the decline of the old great powers, such as France? Are we somehow being replaced by new powers?

Once again, there are powers that are trying to question, or even review, the rules of the game. And I think that the influence of the former colonial powers is diminishing considerably.

I listened to the interview given last week by Félix Tshisekedi, the President of the Democratic Republic of Congo, to Darius Rochebin, in which he said: “I’m going to welcome Russia and China with open arms, I don’t want my former colonial power any more”.

France has historical conflicts with Algeria. The President of the Republic made remarks that displeased Algiers concerning the “memory rent”, which aroused the mistrust of the Algerian President, who is now turning to Russia and China. Relations with Algeria are not at their best, although France is trying to accommodate this country.

Similarly, relations with Morocco are strained by the conflict over the Western Sahara. Although most countries recognise Morocco’s sovereignty over the Western Sahara, France adopts a more moderate and cautious stance to accommodate Algeria. As a result, relations with Morocco are also difficult. But recently, Stéphane Séjourné, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, travelled to Morocco to try to rebuild relations with Moroccan diplomacy.

Finally, we have been driven out of the Sahel. For example, look at what is happening in Mali, and not without the help of our Russian “friends”. They have carried out fairly extensive disinformation campaigns, manipulating the population and fuelling hatred of France.

Let’s also look at Niger, and how France, in a way, tried to keep its ambassador there. Things went very badly and France was literally driven out.

If I’m not mistaken, the United States is also leaving Niger?

Yes, they are leaving Niger, but appointing a special representative. But it is clear that Russia is now gaining a foothold in this part of the world.

France has shown considerable courage in deploying the Barkhane force to fight Islamist terrorism. We have lost more than 50 French soldiers on the ground. We have not succeeded in eliminating Islamist terrorism, which remains a major challenge. It was a very courageous action, but unfortunately we had to leave.

The situation ended in failure because the concept of “Franceafrique” is no longer relevant. From General de Gaulle to François Mitterrand, there was this “Franceafrique” unit at the Élysée Palace, which tried to maintain official relations, but also sometimes ambiguous links, particularly for commercial matters. We were accused of neo-colonialism because of this. And that’s precisely what these countries want to avoid with the powers that are there today.

When Emmanuel Macron came to power in 2017, something he said struck me. He said: “I want an end to Franceafrique”. But in reality, we have continued our methods as before, and the fact that we have been driven out of part of the Sahel actually shows that Emmanuel Macron’s wishes have been fulfilled.

We have been driven out of the Sahel, and much of sub-Saharan Africa. We are resented, even though the Francophonie remains a very important part of French culture. Nevertheless, this clearly signifies the end of a certain way of operating with these countries, the end of colonialism and neo-colonialism.

However, what these countries have not fully understood is that they are going to replace neo-colonialism with a new form of colonialism, involving Russia and China. But they will realize this later.

Moreover, it is important to emphasize that France remains a major nuclear power and a permanent member of the Security Council. We have often been criticised, but it is entirely legitimate for the President of the Republic to speak out as the leader of a major nuclear power. This is not always well received, but we have the ability to assert our viewpoint among the United States, Russia, China, and other major powers.

In reality, we are a middle power, but because we possess nuclear weapons, we can carry weight in discussions and take a seat at the table with the major powers. Specifically, in the Israeli-Arab conflict, it would be very interesting for France to make an ambitious proposal in favour of the creation of a Palestinian state living peacefully alongside Israel.

France still retains a certain level of influence and can still make its voice heard, but it is true that our power and prominence have somewhat diminished worldwide.

All publishing rights and copyrights reserved to MENA Research Center.