According to Western reports, the Iranian cyber threat to vital national facilities and infrastructure is massive. However, Iran has a wide and highly developed range of cyber capabilities that enable it to launch cyberattacks targeting important national infrastructures and financial, service, educational, and industrial institutions in these countries without leading to an armed reaction or outbreak of a dispensable war.

In light of scientific and technological progress that the world is witnessing, this type of unconventional war has provided a solid ground for Tehran to launch effective and less expensive retaliatory attacks against its opponents, whether inside the country or abroad. Moreover, the development of Iranian cyber capabilities contributed to tightening the regime’s grip on its people, amid the massive popular uprisings in Iran, where it uses cyberspace as a medium to receive uprisings’ updates on the ground.

This research paper discusses the Iranian cyber capabilities that have enabled Tehran to carry out harmful cyberattacks against its opponents from governments, organizations, to individuals. It starts with a brief look at the definition and methods of cyber warfare and then sheds light on the motives that got Iran to develop such skills. It also discusses the most important internal and external goals that the Iranian cyberattacks targeted during the past decades, placing a critical reading of Iran’s cyber capabilities on the international level, and providing a set of conclusions.

The Research Pinpoints:

- A brief introduction to cyber warfare

- The evolution of Iran’s cyber capabilities: Motives and goals

- Iran’s cyber capabilities on the international level

- Summary and conclusions

A brief Introduction to Cyber-warfare

The classic definition of a cyberattack is any attempt to gain access to private and confidential information or to disrupt computer networks. In other words, any type of attack launched from a computer or network of computers to a device or network of other computers is called a cyberattack.

There are many ways to launch cyberattacks, but most of them fall into seven categories:

Malware

Malware is a part of code, like any other program, developed by one or more programmers. The purpose of this malware is to sabotage, spy on information and steal it, and remotely control the victim’s computer.

In short, malware aims to destroy a computer or a network of computers and this type is one of the most dangerous methods of cyber warfare. Iran has used this form of attack to target ethnic and religious minorities. Reports indicate that Iranian government’s hackers have used malware to attack more than 100 people, including Turkish human rights activists and Ghanabadi Dervishes (a Sufi Sect).

Phishing

This method relies on obtaining a website’s password by creating a fake website or webpage, but it looks exactly like the original site.

In phishing, the letter F is replaced by the letter PH to refer to the concept of “cheating”, just like a fisherman who deceives the fish he catches with bait. The Iranian government’s hackers have been using phishing for years as they have great experience in this field.

Ransomware

Ransomware is similar to malware in many ways, except that it is created with the purpose of blackmail. In this type, the attacker usually encrypts the victim’s computer information in an unusable way and asks the victim for money to decrypt it. They simply take computer information as a hostage to demand its release.

Wannacry was one of the most famous and destructive ransomware programs. In 2017, Ransomware affected nearly 200,000 computers around the world, including Iran, and the attackers demanded that victims pay 300 dollars in bitcoin to unlock computers.

Distributed denial of service attacks (DDoS)

An Arab proverb says, “One hand does not clap,” and this proverb applies perfectly to the method of denial of service.

Each website or online service can only respond to a limited number of requests. For example, when you visit the MENA Research and Studies Center website, it can only respond to a certain number of visit requests. When this site or service falls under great pressure, it will lose control like any person who is exhausted from workload, hence it will not be able to respond to requests. The purpose of such an attack is to make a website or any service connected to a computer network unavailable or inaccessible, which means disabling the service.

Man in the middle

A Man-in-the-middle attack is eavesdropping. Imagine that you are in contact with a friend through an intermediary that has earned your trust. The intermediary manages to convince both of you that you have a private and direct relationship, but he practically hears all your conversations and may change them in some cases. Such an action is called middleman. In August 2011, Google announced that it had successfully identified an attack by Iranian government hackers and prevented it from using this method to attack political opponents and human rights activists.

SQL injection

This approach is a direct attack on databases. A “Structured Query Language” is a language for extracting data from databases by finding security glitches to steal information, including passwords or to destroy information stored in the databases.

Zero-day exploits

It is making use of security glitches in computer programs that have not been discovered by the manufacturer or they are discovered but not yet fixed. The most popular of such attacks was the Stuxnet virus, which targeted the uranium enrichment facility in Iran. The makers of Stuxnet discovered four security glitches in the facility’s Windows Operating System and they planned to exploit these four vulnerabilities to disrupt and destroy the uranium enrichment process in Iran.

The evolution of Iran’s cyber capabilities: motives and goals

The Stuxnet virus attack on Iranian nuclear facilities in 2010, which the US and Israel were accused of, was one of the most sophisticated cyberattacks in recent history. It caused serious damage to the equipment controlled by the target computers and set the Iranian uranium enrichment program back several years. Hence, a new type of cyberattacks was introduced.

In fact, the Stuxnet attack was the main reason in motivating Iran to develop its cyber capabilities. It unleashed Iran’s position in the cyberattacks world, to the point that Iran has invested heavily in building defenses and cyberattack skills at the same time.

Since then, Iran has been accused of committing several cyberattacks, using the above-mentioned methods, depending on the nature and circumstances of open cyber warfare. However, many other motives have forced the Iranian regime to develop its cyber skills amid the local, regional, and international variables it faced during the past decades.

Motives

Protecting the ruling regime through cyber repression of dissidents and uprisings

Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has always believed that Washington is seeking to overthrow the ruling regime by inciting the masses modeled after the Velvet Revolution that toppled the Czechoslovak Communist regime in 1989. Furthermore, with the early and effective use of the internet and social platforms by the regime’s opponents in Iran, the extremists in Tehran got the impression that the foreign forces are planning to topple the ruling regime using new internet technologies.

Based on this argument, Iran’s first cyber operation was launched during the 2009 Green Revolution amid concerns that the stability of the regime was exposed to external threats and that the Internet, to which Western governments supported unrestricted access, would facilitate this.

Nevertheless, considering the authorities’ expulsion of foreign media from Iran, spying on mobile networks and arresting the most prominent opponents, the Internet became the main channel for communication and coordination during the Green Revolution that broke out in 2009. Furthermore, the emergence of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter and messaging applications, such as Telegram, posed a major threat because it was a challenge to the Iranian government’s long-standing monopoly on media and communication equipment.

Moreover, during the Green Movement, hacker groups loyal to the Iranian regime used a multi-pronged strategy that included hacking websites and monitoring networks. As such, from December 2009 until June 2013, the so-called Iranian cyber army sent messages in support of the government to opposition websites, Israeli commercial companies, independent Persian media, and social media platforms.

At a time when human rights defenders and opposition leaders were calling for massive popular protests, important sites, such as Twitter were subjected to cyber warfare (denial of service), which deprived users of access to these sites temporarily. The Iranian government also sought to spy on its opponents, by sending malware alleging that it contains information related to upcoming protest programs. At that time, an Iranian hacker hacked the Dutch security company DigiNotar, which facilitated the issuance of fake encryption certificates (phishing) that allowed Tehran to spy on all Gmail users inside the country, which was considered one of the biggest security breaches in Internet history.

Most of the victims of Iranian cyber operations are either Iranians or large numbers of Iranian immigrants, whom the country’s leaders classify as enemies and they fear them. However, the goals of cyber-surveillance in Tehran were not limited to those whom the regime considers opponents seeking to topple the regime, but also included non-political and even cultural institutions, Iranian governmental organizations and political reformist figures , thus cyber espionage and subversive attacks on government opponents have shown Iranians that their online activities are not beyond the government’s reach.

Flexing muscles

During the past decades, the virtual world has turned into a new battlefield in what could be called the Cold War between the United States and its allies on one and Iran on the other side.

The Iranian government may have become the target of the most destructive cyberattacks by the United States and its allies, but the security groups of the Revolutionary Guard and the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence have managed to develop their skills in carrying out cyberattacks that target Iranian opponents at home and abroad, companies and non-governmental organizations, as well as economic, defense, and financial institutions in various countries, including Germany, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States.

However, Tehran, which has consistently used its militias to prove its power in the region, often denies its participation in such attacks, disguising behind cyber proxies or intermediaries to prevent these attacks from being affiliated with it. Nevertheless, despite this denial, Iran has openly invested in local cyber capabilities for offensive and defensive purposes, and it is ready to use it to avenge its enemies, or in the event of an armed war.

Low-cost War – cyberattacks effective and less expensive

Iranian cyberattacks took a relatively late start (after around 2010), where Iran began to hack some websites with low capital, given the state’s limited capacities in this regard. However, Moscow’s influence on democratic institutions and political leaders during the 2016 US elections showed that information warfare can be waged by using rudimentary solutions that have low costs, great impact, and effectiveness at the same time. From this standpoint, Iran made use of the shortcomings or lack of preparation of vulnerable targets inside and outside the country, including Saudi oil companies, Middle Eastern countries, and US banks.

The important point is that these operations often led to large financial losses, but the methods used to destroy data or disrupt access to websites were relatively simple, and of low cost, not to mention that Tehran’s attacks against external interests were espionage and sabotage attacks against vulnerable targets in the competing countries.

Iran indeed has shown that militarily weaker states can use aggressive cyber campaigns to fight its advancing enemies, on whom Tehran has imposed retaliatory costs to prove their ability.

Targets

External targets

Since Iran is unable to wage a fruitful or deterrent conflict against their well-prepared opponents, it launches destructive and opportunistic cyberattacks to demonstrate its ability to retaliate. However, Iranian cyber operations could threaten the infrastructure and economic resources of its opponents who do not have sufficient support and preparation in this field. Saudi Arabia, Denmark, Germany, Israel and the United States are among the countries that have publicly disclosed the spying efforts of Iranian groups against their governmental, military or scientific institutions.

Tehran also targets neighboring countries throughout the Middle East, but despite the diversity of cyber threats posed by the Iranian government, its behavior patterns, including its objectives, have generally remained constant over time.

The United States and Europe

In September 2012, a group calling itself “Izz Ad-Din al-Qassam Cyber Fighters” launched a cyber campaign (denial of service) against the US financial sector. Before the campaign, attackers were exploiting software vulnerabilities of thousands of websites to create an attack platform under their control. With this army of servers in the host companies, the attackers were able to expose their targets to heavy and devastating Internet traffic.

In the first phase of Operation Ababil, this group targeted the US banking infrastructure, where American banks were subjected to traffic equivalent to three times their basic capacity, causing their systems and databases to stop working.

Although the later phases of Operation Ababil (until phase 4 in July 2013) were not very fruitful, as the financial sector was constantly working to improve its defense system according to the FBI, Operation Ababil prevented hundreds of thousands of bank clients from accessing their accounts for long periods, which resulted in losses estimated at tens of millions of dollars.

Besides, a report issued by the US National Security Agency explains the motive behind Operation Ababil, saying: “Intelligence signals show that these attacks were retaliation for Western activities against the Iranian nuclear sector, and high-level Iranian government officials were aware of the attacks.”

Furthermore, the cyberattacks did not stop after Operation Ababil, the most destructive cyberattack on the United States, and it was alleged that Iran had access to the unclassified Internet of the United States Marine Corps for several months since August 2013.

In the 2016 edition of the German Interior Ministry’s annual security assessment, the German government identified Iran as a new source of cyber espionage against the country. This assessment was in line with reports that the German parliament was affected by a malware operation targeting readers of the Israeli newspaper “The Jerusalem Post”.

On February 14, 2020, the cybersecurity firm “FireEye” concluded in its research that Germany is now considered an attractive destination for cyberattacks supported by governments such as Russia, China and Iran, due to its political importance in Europe and the world.

However, Iran has rarely succeeded in infiltrating the infrastructure of US and European governments, especially the highly secured networks, as the government agencies in these countries are usually heavily guarded, so that agents of the Iranian threat cannot penetrate them. As a result, Iran pursued simpler goals, in an attempt to target the personal emails and social media accounts of US government employees using the method of (targeted phishing). For example, Iranians attempted to hack into the personal email accounts of members of the US team during the nuclear negotiations.

Nevertheless, after the 2016 US presidential election, Iranian threat agents focused on former Obama employees, Donald Trump campaign supporters, conservative media institutions, and political candidates to learn about the new US administration. Later on, Iranian phishing attacks targeted Iranian opponents in the US Congress while it was considering new sanctions against Iran.

In general, Tehran seeks to target employees and organizations of foreign governments focusing on Iran in the United States or Europe, concerning Iranian politics or the Farsi-speaking media, such as Radio Voice of America or Radio Farda.

An observer of the graph of Iranian cyberattacks finds that covert activities and retaliatory attacks have decreased between Washington and Tehran since the signing of the nuclear agreement in 2015. Tehran has focused more on political opponents and regional enemies, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia. However, these activities have returned during the reign of Donald Trump, especially after Iran shot down the US drone on June 20, 2019, and the killing of Qassem Soleimani in an American raid near Baghdad Airport in early 2020.

Moreover, just one day after Qassem Soleimani was killed, the US Department of Homeland Security issued a statement warning of a cyberattack by Iran, saying, “Iran has a powerful cyber program that could pose a threat to the United States. Iran can at least disable some of the vital infrastructures of the United States for a limited period.”

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Due to the tense relations between Tehran and Riyadh since the victory of the revolution in Iran, Saudi Arabia was ranked first among the countries that have been subjected to cyberattacks by Iranian agents supported by the government. Since the beginning of Iran’s cyber operations activity, Saudi political and economic institutions have been penetrated by Tehran with the aim of espionage and sabotage and Saudi Arabia was one of the most susceptible to attacks in the various reports that talked about malware and campaigns of stealing accounts and passwords by Iranian threat agents. This reflects the deep ideological and geopolitical differences between the two countries, as well as Saudi Arabia’s persistent vulnerability in cyberspace.

The Iranian cyberattack on Saudi Aramco facilities on August 15, 2012 (and the similar attack on the Qatari RasGas company two weeks later) was a clear example of how Iran used cyberattacks to avenge its enemies, that caused them huge financial losses. Moreover, Iran used unknown cyber agents to deflect the accusation from it in these attacks.

Iran may not always be able to defend itself against the advanced cyber capabilities of the United States. However, it can impose heavy costs on its allies, and this is Iran’s message that wanted to convey through the “Shamoon” attack, which incurred hundreds of millions of dollars in losses, as it penetrated tens of thousands of computers at Saudi Aramco. Moreover, the cycle of devastating retaliatory covert attacks seen in Shamoon and Ababil reflected the Iranian security tactics in the virtual world.

For example, between 2010 and 2012, many Iranian nuclear scientists were assassinated in mysterious circumstances. These actions were attributed to the United States or Israel. In response, Tehran tried to assassinate Israeli officials in unexpected places, such as Georgia, India, and Thailand, but failed to do so.

This cycle demonstrates that Iran learns from the attacks and seeks retaliation in the same way. This provides potential benchmarks for understanding Iran’s signals and motivations for carrying out malicious cyber operations. On the other hand, compared to other enemies of Iran (namely the United States and Israel), the Saudi government and economic institutions still have to put in place appropriate systems and protocols to increase its national cybersecurity, to put an end to Iranian cyberattacks that only damaged Saudi economic institutions, at a time when It fails to inflict heavy losses on the United States.

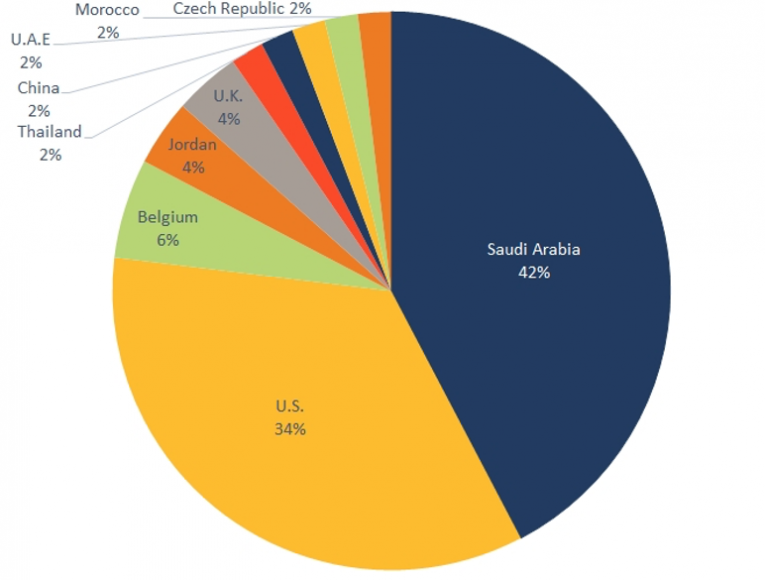

Moreover, what confirms this is the Shamoon 2 attack that destroyed from November 2016 to January 2017 databases and files owned by both the Saudi government and the private sector, including the Civil Aviation Authority, the Ministry of Labor, the Saudi Central Bank, and natural resource companies . As well as the APT 33 attacks carried out by a group known as (Elfin Group) and continued from 2016 until 2019, striking more than fifty organizations (most of them working in vital fields and energy), most of them distributed in Saudi Arabia, the United States, and several other countries, as the chart shows below :

Israel

Despite all the anti-Israel emblems pursued by Iranian foreign policy, many Iranian cyberattacks against Israeli institutions, carried out with the aim of destruction and espionage, were not successful. This is, with no doubt, due to the high level of Israeli cyber defense skills, which pushed Tehran to settle for attacking simple targets which are mostly “non-military”, by denial of service or phishing techniques.

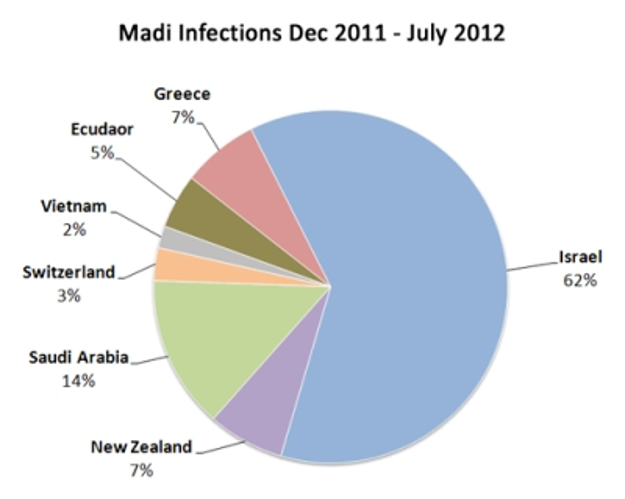

Nevertheless, one of the successful Iranian cyber operations against Israel was the Madi Campaign(MalwareMadi) in 2012, in which investigations indicated that its command and control servers were run by Iran, and they damaged Israeli institutions in the first place, and Saudi Arabia too, as shown in the following chart:

Furthermore, Iran launched cyberattacks (denial of service) against Israel, which are similar in tactics to the attacks it launched against the US and opponents of Tehran. Iran has also phishing targeted academic institutions, national security officials, diplomats, members of the Israeli parliament (the Knesset), Israeli airlines, and the American Israel Public Affairs Committee.

The table below shows the most important Iranian cyberattacks during the past two decades:

| Operation Name | Period | Victims |

| Hacking Social Media Platforms | 2011- 2016 | A cyber operation carried out through fake accounts and robots in social media platforms to generate misinformation in American Society. |

| Ababil | December 2011 – May 2013 | The first denial-of-service attacks against U.S. banks |

| Cleaver | 2012 – 2014 | An operation for industrial and governmental espionage purposes. |

| Shamoon | August 2012 | Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil company, has data destroyed by the malware agent Shamoon. |

| Bowman | August – September 2013 | Bowman Company in New York was hacked. |

| Saffron Flower | 2013 – 2014 | The campaign targeted information technology systems in the US Defense industry and the defectors from the Iranian regime who are aboard. |

| Sands Corporation | 2014 | Cyberattack against Las Vegas Sands Corporation |

| Thamar Reservoir | February 2014 | Cyberattack that targeted activists, research centers, and journalists in the Middle East. |

| APT OilRig | 2017 -2018 | An Iranian organized threat group operating primarily in the Middle East by targeting organizations in this region from various industrials. |

| Shamoon 2 | November 2016 – January 2017 | Cyberattacks against Saudi Arabia are renewed in Shamoon 2 |

| Leafminer | 2017 -2018 | Espionage campaigns targeting Middle Eastern regions. |

| APT 33 | 2016 – 2019 | Threat group that targets private-sector entities in the aviation, energy, and petrochemical sectors |

Internal goals

Iran was one of the first countries in the Middle East to have an Internet connection and more than half of its population has been using the Internet since March 7, 2017. However, this has posed a great challenge to the security system in Tehran since the majority of Iranians avoid using traditional means of communication which were under the full control of government security agencies.

At the same time, Iranian Internet users were able to use social networks and private chat applications, taking advantage of Internet platforms located outside Iran and encryption technologies to protect their communications from eavesdropping, which provided them with a bigger room of social freedom.

Nevertheless, the Iranian government has always tried to force foreign companies to provide them with information of their users, but it has not succeeded in this endeavor, while domestic alternatives to foreign services such as Telegram and WhatsApp have failed to attract users, including Iranian officials, and millions of Iranians living inside and outside the country, which made most Iranian communications and personal activities to be out of the government’s reach during the first two decades after the victory of the revolution in Iran.

This situation of lack of full control has pushed the security system in Tehran to prompt its cyber operations and be more flexible amid the changes in the modern programs that the virtual world made available for the Iranian masses.

For example, after most Iranians resorted to using Telegram, considering it is a relatively safe program compared to other chatting programs, the Iranian threat agents turned their attention to it, seeking to carryout phishing attacks to steal the passwords and names of Iranian users of Telegram.

Furthermore, Telegram is one of the most popular chat programs in Iran. It is used by more than twenty million users inside Iran, and despite all the conflicts that the Iranian government has waged with the administration of Telegram, this application is still easily available inside Iran, unlike many other chat applications that have been banned. However, the Iranian government’s leniency towards the Telegram application and its users, and allowing them to use it inside Iran, was an evidence of the big security breach that the security government was practicing on its citizens.

According to some official reports, in 2016, threat agents associated with the Iranian government managed to reach more than 15 million Telegram users in Iran . This means that the application’s users were subject to strict government control, including wiretapping and monitoring of all their communication. Hence, this explains the indulgence of the security government in Tehran to allow users to communicate through this application without any obstacles.

In general, the planned cyberattacks carried out by different groups of Iranian government threat agents over different periods of time have focused on a set of objectives:

- Government officials and reformist figures

- Media figures

- Major Iranian opposition groups (People’s Mujahedin of Iran “PMOI” is an example)

Government officials and reformists

One may think that Iranian officials may be a red line for hacker groups affiliated with the Revolutionary Guard and the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence, but the documents published by the BBC Persian website in 2018 show that these security groups do not differentiate between Minister of Iranian Foreign Ministry Javad Zarif and any human rights activist working outside Iran, or between an exiled Iranian opposition and any US, Saudi, or Israeli military and economic establishment.

This shows the size of the profound powers of the security state that governs Iran, which enables any officer in the Revolutionary Guard, or perhaps an intelligence agent in the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence, to give an order of a cyber (espionage) attack against those close to the President of the Iranian Republic, Hassan Rouhani, including his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Javad Zarif, his brother and advisor Hossein Fereydoun, Majid Takht Rahwanji, Abbas Araghchi, Husamuddin Ashna, and several other officials close to the Rouhani government, who have been subjected to cyberattacks led by Iranian threat agents.

As such, the cyber campaigns targeting members of Rouhani’s government, and prominent reformist figures within it, demonstrate the importance of electronic surveillance as a tool in hands of the extremist security government that enables it to control potential competitors for power by collecting sensitive information about their lives to blackmail, humiliate them or use their online accounts as a platform to attack other personnel.

Nevertheless, the Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs is a prominent and clear example of espionage inside the government. Since the beginning of the Rouhani administration, Iranian diplomats have often been the target of phishing campaigns, especially that these activities coincided with accusations made by media of the Revolutionary Guard of betraying Iran’s interests after the signing of the nuclear agreement. One example of this was the arrest of Abdolrasoul Dorri- Esfahani, a member of the nuclear negotiation team, on charges of espionage.

Media Figures

Iranian cyber operations are regularly focused on journalists who work with reformist media and international satellite networks that are outside of government control and its strict oversight. Many of the Iranian threat agents have carried out numerous operations against foreign journalists residing in Iran, as well as Iranian journalists working for prominent publications such as Al-Sharq newspaper, by executing various campaigns aimed at stealing accounts and passwords.

Likewise, independent journalists inside Iran are regularly harassed by fake figures who send them malware to infiltrate their accounts and spy on them. These cyber campaigns often target publications that eventually get closed or journalists who get detained by Iranian security forces.

Moreover, what happened to Jason Rezaian, a former Washington Post correspondent in Iran, shows the focus of the pro-government threat agents on the foreign press operating in Iran. Rezaian was a target of Iranian cyber campaigns “flying kitten hackers” . They tried to infiltrate Rezaian’s Hotmail and Gmail accounts several times with fake security accounts by stealing usernames and passwords before his arrest on July 22, 2014, where the Revolutionary Guard sentenced him to 18 months in prison.

Main Iranian opposition groups

Iranian opposition groups, especially People’s Mujahedin of Iran (PMOI) and the National Council of Resistance of Iran, have been subjected to reprisal attacks that varied between the physical liquidation of their cadres abroad, the brutal arrest, and execution campaigns of their supporters inside Iran. The PMOI, as the largest Iranian opposition group that has wide popularity and can mobilize and organize large demonstrations inside Iran, the Iranian regime deals with it as its archenemy and seeks to get rid of its leaders by any means. This is what happened in the recent failed assassination attempt of the President of the Republic who was elected by the National Council of Resistance of Iran, Maryam Rajavi, in 2018 in a terrorist plot in Paris.

For this reason, the PMOI and its cadres have been the most prominent victims of cyber campaigns organized by Iranian threat agents who had one goal, which is to steal information from Iranian opposition groups in Europe and the US and spy on Iranian dissidents who often use mobile applications to plan and organize protests.

On December 18, 2020, a report published by the American New York Times stated that Iranian threat agents use a variety of hacking techniques, including phishing, but the most common method is to send enticing documents and applications to carefully selected opposition targets.

For example, Iranian threat agents sent the National Council of Resistance of Iran a document in Persian titled “The Regime Fears the Spread of Revolutionary Guns. Docx”, referring to the conflict between them and the regime. These documents contained a malicious program that activated several spyware commands from an external server when recipients opened them on desktop computers or mobile phones.

On the other hand, the spyware enabled attackers to access almost any file, record clipboard data, capture screenshots, steal information, and download data stored on WhatsApp as well. Moreover, Iranian attackers discovered weaknesses in the installation protocols of many encrypted applications including Telegram, which was considered relatively safe, and enabled them to steal application installation files and create logins on Telegram to activate the application in the names of victims on another device, which allowed the attackers to covertly monitor all the victims’ Telegram activities.

Iran’s cyber capabilities in the international reality – critical analysis

Before information technology became widely available, the Iranian government focused its intelligence operations abroad on recruiting agents to spy and assassinate political opponents or diplomats of their rivals, and plan terrorist plots abroad. However, these intelligence operations used to cause international embarrassment to Tehran, especially in case of arresting the attackers.

Nevertheless, with the emergence of the information revolution and the improvement of Iranian cyber capabilities, cyberattacks provided less dangerous opportunities in gathering intelligence information and retaliation of what Tehran considers an internal or external enemy, with a great capacity for denial compared to covert intelligence operations. Over the past decade, cyber operations have become a primary tool of Iranian policy for purposes such as espionage, retaliation, and internal repression, following a consistent pattern of threats to a range of specific targets.

Despite this, Iranian cyberattacks looked rudimentary compared to government-sponsored attacks in developed countries, not to mention that the amount of expertise, logistics, and investment required to carry out operations such as the Olympics (Stuxnet virus) still greatly exceeds the capabilities of Iranian threat agents. Unlike the US and Israeli cyber operations, which have been executed by professional intelligence services backed by billions of dollars, Iran’s offensive and defensive cyber abilities remain chaotic and underfunded. Thus, although Iran often carries out destructive attacks to exert pressure or retaliation, its opportunities remain limited and weak to threaten its advanced foes, especially the US and Israel.

What confirms this theory is the continuous and repeated Iranian cyberattacks against Saudi Arabia with weaker power and less cyber defense readiness, compared to their US and Israeli counterparts. On the other hand, what Iranian officials allege about their country’s military strength, including cyber capabilities, is an exaggeration and Tehran has rarely adopted responsibility for cyberattacks, it rather made contradictory statements about its cyber position.

Although Iranian media always emphasizes the country’s defense and offensive capabilities in the cyber field, citing reports published on Western media , Tehran does not officially acknowledge the cyberattacks it carries out against its enemies, and it always denies that it suffers any losses resulting from a cyber counterattack.

Furthermore, the official** rhetoric of the Iranian regime seeks to exaggerate its cyber capabilities, but at the same time, it presents itself as a victim of foreign aggression (US and Israeli), using the reports of devastating cyberattacks directed against Iran during the past decades.

For example, when the United States accused Iran of carrying out the devastating attack on American banks (Ababil), Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Hossein Jaberi Ansari responded that “The US government, which launched cyberattacks on Iran’s peaceful nuclear facilities, exposed the lives of millions of innocent people to the risk of an environmental disaster. Moreover, the US is not in a position to accuse the citizens of other countries, including Iran, without the existence of justifiable evidence.”

Nevertheless, despite all these allegations, Iran has not succeeded in building a comprehensive cybersecurity industry. Also, in terms of investing in defense or developing national policies to secure critical infrastructure, it still lags behind advanced economic systems and their main competitors in the region.

Furthermore, the Iranian government spent tens of millions of dollars on cybersecurity in recent years. However, its investments appear to be failing considering the billions of dollars that the US government spends annually or the hundreds of millions of dollars that US banks spend separately. Even if Iran focuses on improving its defense capabilities, it will still face significant constraints due to sanctions and lack of specialized skills. Moreover, given the experience of Iran’s enemies, the Iranian government’s statements look suspicious regarding fast-tracking and preventing foreign infiltration into Iranian networks.

Iran is considered a third-class country in its cyber capabilities, as it lacks advanced cybersecurity institutions that can conduct successful campaigns like other countries such as China, Israel, Russia and the United States.

Despite that Iran executes some successful cyber operations, but they reflect chaos lack of experience in these operations that cause limited damage and can be repaired in a short time. The political isolation and economic sanctions imposed on Tehran have prevented the state from obtaining technology and expertise from foreign countries and companies. Moreover, it seems that Iran has failed to increase its cyber capabilities due to the severe sanctions, as it is unable to obtain the necessary technologies and train skilled experts in the cyber field.

Although US officials and some cybersecurity companies believe that Tehran has received technical assistance from countries such as Russia, North Korea, and China, there is no evidence of significant cooperation with these countries in the field of developing Iranian cyberattack capabilities. It is also true that Iran obtained network monitoring devices from Chinese telecommunications companies and entered into cooperation agreements in the field of cybersecurity with Russia, but these relationships differ from providing Tehran with cyberattack techniques. In addition, Iran has shown its talent in social engineering (deceiving victims to fall into hacking traps), but this does not mean that they obtained this talent from other countries. In fact, Iranian threat agents have repeatedly used ready-made professional hacking tools to run their campaigns. However, there is no evidence that Tehran obtained malware from foreign governments. Moreover, none of the attacks that were publicly recorded or covertly monitored prove the use of tools or resources beyond the capacity of Iranian threat agents.

Summary and conclusions

Over the past four decades, the escalating tensions between Iran and the United States have taken a new turn within cyberspace, as Tehran has been one of the main targets of the United States’ destructive and unique offensive cyber operations, and at the same time, the cyberattacks carried out by Iran were one of the most complex and important attacks in the history of Internet.

The above leads us to the following conclusions:

- Cyberattacks have become one of the main tools of governance in Iran, as they have provided less dangerous and costly opportunities for Tehran to gather information and take revenge on enemies inside and outside the country.

- The set of tactics, tools, and Iranian threat agents during the internal challenges that the regime has faced in the past decades have reflected the cyber situation of Iran in facing a wide range of internal and external threats. However, the consistent features of Iranian cyber operations showed that there were no clear boundaries between campaigns against internal opposition and foreign enemies. In the campaign against the US defense industry, the Iranian threat agents used the same infrastructure and tools used in campaigns targeting Persian language programs concerning the advancement of women. Moreover, the same malware used in destructive attacks on Saudi government institutions has previously been used to monitor members of the opposition Green Movement.

- While Iran uses its proxy militias to prove its regional power in the region, it often uses its cyber proxies to conceal its electronic operations to officially deny its responsibility, despite clear indications that such operations were carried out by the cyber groups of the Revolutionary Guard and the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence.

- Although Iran does not possess the advanced cyber capabilities that countries such as the United States, Israel, Russia, and China possess, its sabotage cyber operations have demonstrated the shortcomings and lack of preparation for vulnerable targets inside and outside the country, especially Saudi interests, and that information warfare can be waged using primitive and simple tools and tactics, in order to impose heavy retaliatory costs on its enemies.