While the mullah leadership in Iran blames Salman Rushdie himself and his supporters for the murder attack at the end of last week, the Muslim associations in Europe are silent and do not condemn the assassination attempt. Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesman told in a press conference that freedom of expression does not justify Rushdie’s “insults” of religion in his works. He only has information about Rushdie’s attacker that can be found in the media.

Rushdie was attacked and injured on an open stage at an event in upstate New York on Friday. He was cared for on site by a participant in the event who was an emergency doctor and then taken to a hospital. Despite the various knife wounds in his face, neck and abdomen, the Nobel Prize winner is on the mend and no longer needs artificial respiration. The 24-year-old attacker was arrested.

Rushdie, who was born in India, was criticized in the Islamic world primarily for “blasphemy” in his book The Satanic Verses. In 1988 the book was banned in many Islamic countries. In 1989, the then spiritual and political leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a so-called “fatwa” for the killing of Rushdie and even placed a bounty on Rushdie and those who were involved in the book. The Iranian leadership later withdrew from this appeal to all Muslims. Nevertheless, the Japanese translator of the “Satanic Verses” was killed by an assassin who invoked Khomeini’s fatwa.

After the attempted murder, the ultra-conservative Iranian newspaper “Kayhan” praised the attacker as a “brave man” who “ripped open the neck of the vicious” Rushdie with a knife”. Other media in Iran made similar statements. There were also statements of support for the perpetrator in Pakistan.

The attacker, identified by police as Hadi Matar, appeared for a court hearing in Chautauqua on Saturday. Through his lawyer, he pleaded not guilty to the charge of “attempted murder” against him. It therefore remained unclear whether the 24-year-old acted as a result of the 1989 fatwa. Matar’s next court date is scheduled for next Friday.

The attack caused great horror in the western world. US President Joe Biden condemned the “cowardly attack” and praised Rushdie for his “refusal to be intimidated or silenced”. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz spoke of a “disgusting act” and praised Rushdie’s fearless commitment to freedom of expression.

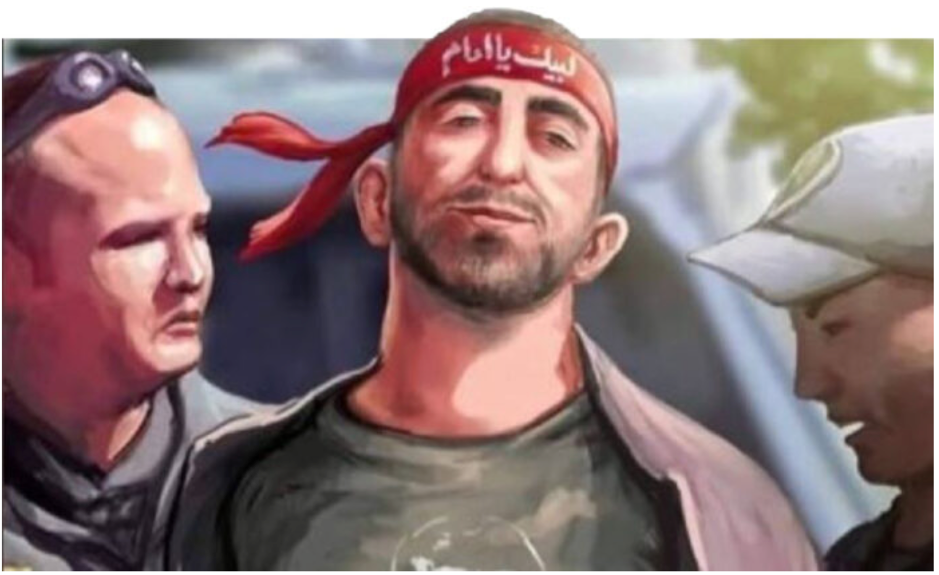

Islamist extremists also misuse social media for agitation and hate speech. On Twitter, Muslim fanatics pay homage to the assassin, who has been stylized as a jihadist icon with falsified photos of his arrest. The Arabic hashtag “Hadi Matar represents me” is the Muslim counterpart to “Je suis Charlie” after the massacre in the Parisian Charlie Hebdo editorial office in 2015, but this time in reverse of perpetrator and victim: It is not the dead or injured who are remembered, but the assassin is heroized.

“Congratulations, God bless you for this work,” reads the hashtag. “Peace be upon the one who quietly rained stab wounds on Satan’s body,” wrote another. Warnings are also being circulated on Twitter: “Anyone who dares to insult Islam and Mohammed must expect a similar fate. It’s not terrorism, it’s heroic defense.”

As of Monday evening, according to research, Twitter had only deleted a tweet referring to the company’s policy violation, in which the assassination attempt was described as “the greatest good news of the century”.

European Islamic associations have not yet commented on the attack. On the day of the attack and the following weekend, the Central Council of Muslims in Germany (ZMD) published statements on Islamophobia in Germany and the increase in racism in the country, nothing on the attack. The same applies to the Bund der Muslimische Jugend (BDJM) and the Ditib association, which is particularly strong in Germany and represents Turkish Muslims in the country.

Even if the Islamic Faith Community in Austria (IGGÖ) has not yet issued a press release on the assassination attempt against Rushdie, its President Ümit Vural has at least expressed his sympathy via Twitter and emphasized freedom of expression as a human right. A similar picture in France, Belgium and Scandinavia.

If one researches the current statements by politicians in Germany, Austria, France and Belgium with a migration background, the picture is just as ambiguous: those who repeatedly critically examine Islam and its role in the 21st century, advocating a secular society, have expressed their condolences. Others, who in turn rely on the religious communities in their political work and communication, remain silent. It is precisely these multipliers who should send a signal to their electorate about the values that are decisive in a European society. Unfortunately, this hope is in vain!

All publishing rights and copyrights reserved to MENA Research and Study Center.